About Machu Picchu – Complete Travel, History, Trekking and Sustainability Guide

About Machu Picchu:

Machu Picchu is more than a postcard; it is a living classroom of history, architecture, astronomy, hydrology, botany and anthropology. Set high in the Peruvian Andes at about 2,430 metres above sea level, this 15th‑century citadel balances on a knife‑edge ridge between two prominent peaks—the old peak called Machu Picchu and the young peak known as Huayna Picchu.

When dawn breaks, wisps of cloud wrap themselves around stone terraces, and the sunlight paints the Urubamba Valley gold. Standing on a ledge near the Guardhouse, you sense both the audacity and serenity of the Inca builders: audacity in constructing a sophisticated estate in such a remote location, and serenity in its harmonious integration with nature.

As a traveller, you’re not just stepping into an archaeological site—you’re walking into a story that spans centuries, from the reign of Pachacuti to the first glimpses of Hiram Bingham and the millions of visitors who come today.

History:

This guide is designed to be your trusted companion from the moment you start dreaming about Machu Picchu to the minute you return home, heart full and footsteps lighter. It goes far beyond listing facts and timetables.

You’ll discover why historians believe Machu Picchu served as a royal retreat, how dry stone walls withstand earthquakes, what time you must enter the site under new rules, how to choose between the Classic Inca Trail and alternative treks, and what to pack for success.

You’ll learn about the Andean cloud forests that blanket the Sanctuary, the porters who power your trek and the laws that protect their welfare, the best seasons for travel and the subtle etiquette of respecting local cultures. We’ve woven in itineraries, checklists, decision frameworks and inspirational anecdotes—along with a healthy dose of caution.

Where information is subject to change (ticket prices, entry rules, transport schedules), we flag it with “Confirm current policy” to remind you to verify details before finalizing your plans.

Origins and Rediscovery

Inca Expansion and the Creation of a Royal Estate

The story of Machu Picchu begins not with its rediscovery in the 20th century but in the flourishing days of the Inca Empire. In the 1400s, the Inca were expanding rapidly under the visionary leadership of Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui, the ninth Sapa Inca. This period saw the transformation of a modest kingdom centred on Cusco into Tawantinsuyu, an empire stretching from Colombia to Chile.

Scholarly consensus suggests that Pachacuti ordered the construction of Machu Picchu as a royal estate and ceremonial centre. Unlike Cusco, which was an administrative capital, Machu Picchu functioned as a retreat where the emperor and his court could perform rituals, host dignitaries and escape the harsh Andean winter.

Incan origins and rediscovery

Archaeologists have dated the structures to the mid‑15th century using radiocarbon samples and analysis of skeletal remains. The name “Machu Picchu” derives from the Quechua words machu (old) and pikchu (mountain), literally “Old Mountain”.

Some early scholars romantically labelled the citadel the “Lost City of the Incas,” but evidence shows local Quechua communities always knew of its existence. It was simply hidden from colonial authorities by geography and vegetation.

Engineering Without Mortar

When you walk through Machu Picchu’s narrow streets, you cannot help but run your fingers along the perfectly joined stones. The builders used dry stone or ashlar masonry techniques, fitting irregular granite blocks together without mortar. The stones were shaped to interlock, and the walls lean inward slightly, which increases stability.

This system allowed the walls to withstand earthquakes by shifting gently rather than resisting rigidly. According to a civil engineer cited by, the resilience of these walls may have been an intentional design or an ingenious side effect.

The city contains approximately 200 structures, from temples and residences to granaries and guard posts. Agricultural terraces cascade down steep slopes, doubling as farmland and retaining walls.

A sophisticated water management network funnels springwater into fountains and bathhouses, illustrating the Inca mastery of hydrology. The builders aligned certain structures, such as the Temple of the Sun and the Intihuatana stone, with astronomical events like solstices, revealing a deep understanding of celestial cycles.

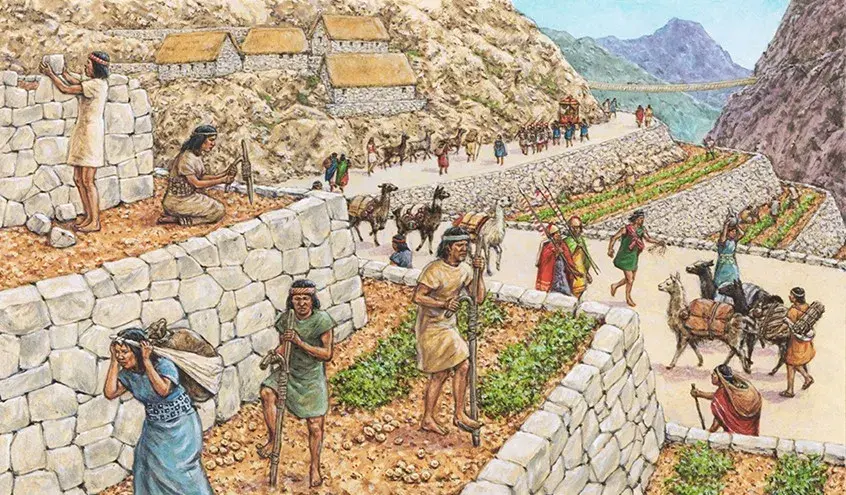

Daily Life in the Citadel

Although Machu Picchu looks like a city, researchers believe its permanent population was relatively small, perhaps a few hundred caretakers and artisans who maintained the estate year‑round. During imperial visits, however, the numbers swelled.

Up to a thousand people may have lived here temporarily, including priests, nobles, soldiers and specialists. They farmed terraces, tended llamas and alpacas, made textiles, brewed chicha (corn beer) and performed ceremonies to honour Inti (the sun god) and Pachamama (Mother Earth).

The site was abandoned abruptly in the 16th century, likely due to the collapse of the Inca Empire following Spanish conquest, epidemics and civil strife. Vegetation cloaked the stone walls, preserving them for centuries. Locals continued farming terraces and grazing animals nearby, but knowledge of Machu Picchu remained within the Quechua communities.

The 1911 Expedition and Global Fame

In July 1911, Yale historian Hiram Bingham III, guided by local farmer Melchor Arteaga, climbed through thick forest to reach the ruins. Bingham believed he had found Vilcabamba, the final refuge of the last Inca. That theory later proved incorrect, but his reports and photographs captured the world’s imagination.

Bingham’s subsequent expeditions led to the removal of artefacts to Yale University, a subject of controversy and eventual repatriation agreements. Today, Machu Picchu’s fame brings economic benefits to Peru but also strains the site, making responsible tourism essential.

UNESCO World Heritage and Mixed Values

In 1983, the Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List for its outstanding cultural and natural value. It meets criteria for being a masterpiece of art and engineering (criterion i), providing testimony to the Inca civilization (iii), embodying a dramatic landscape (vii) and harbouring diverse ecosystems (ix).

The sanctuary encompasses 32,592 hectares of mountain slopes and valleys surrounding the citadel. This mixed designation underscores the necessity of protecting both cultural structures and biodiversity.

Geographical Setting and Natural Environment

Location and Topography

Machu Picchu sits in the Eastern Cordillera of southern Peru, about 75 kilometres northwest of Cusco. The site occupies a saddle between two peaks: Machu Picchu Mountain (Old Peak) to the south and Huayna Picchu (Young Peak) to the north.

The Urubamba River, called Vilcanota in its upper reaches, wraps around the base of the mountain in a sharp bend, forming a natural moat. When viewed from above, the complex resembles a condor with wings outstretched. Visitors can climb Huayna Picchu or the higher Machu Picchu Mountain on separate permits for panoramic views, though the paths are steep and exposed.

The citadel’s altitude of roughly 2,430 metres (7,970 feet) makes it lower than Cusco (3,399 m) but still high enough to cause shortness of breath. The difference matters: many travellers struggle in Cusco but find Machu Picchu comfortable once acclimatized.

The surrounding mountains rise dramatically to 5,000 metres, creating a micro‑climate of cloud forest. On the Inca Trail, the highest point is Dead Woman’s Pass (Warmi Wañusqa) at about 4,215 m, which tests even fit hikers.

Climate and Seasons

Peru’s Andes experience two main seasons. The dry season runs roughly from May to October, bringing clear skies, cooler nights and the majority of visitors. Daytime temperatures hover between 15–20 °C (59–68 °F), while nights in the mountains can drop to freezing. June, July and August are the busiest months; expect long lines for buses and crowded viewpoints.

Climate and Seasons of Machu Picchu

The rainy season spans November to March and sees afternoon showers and lush vegetation. Heavy rains can trigger landslides and occasional train cancellations. February is notable because the Inca Trail closes for maintenance and safety.

April and late September to October are shoulder months that balance moderate crowds and decent weather. Regardless of the month, microclimates mean you might encounter sun, mist and rain in a single day.

Flora and Fauna

The Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu sits at the transitional zone between the High Andes and the Amazon Basin, hosting a mosaic of ecosystems from Puna grasslands and Polylepis thickets to montane cloud forests. Over 400 species of orchids flourish here, including the rare Wiñay Wayna (meaning “forever young”), which lines the Inca Trail.

Ferns, bromeliads and mosses blanket tree trunks. The cloud forest harbours diverse birdlife: Andean cock‑of‑the‑rock, hummingbirds, parrots and Andean guans. Mammals include spectacled bears, pumas, white‑tailed deer, vizcachas (a rabbit‑like rodent) and otters along the river. Reptiles and amphibians are abundant, with brightly coloured frogs signalling healthy ecosystems.

Conservationists consider the area a biodiversity hotspot. However, invasive species, habitat fragmentation and climate change threaten these species. The presence of thousands of daily visitors also impacts flora and fauna; trampling can compact soil and disrupt nesting. Tourists are urged to stay on marked paths and avoid feeding animals.

Conservation Challenges and Management

UNESCO notes that tourism is both a blessing and a curse. Revenue from entrance fees and tour funds conservation and local economies, but overcrowding can erode terraces and degrade trails. To protect the site, Peruvian authorities introduced time‑slot tickets, enforced circuits, and daily visitor caps. They encourage visitors to explore alternative routes and treks to distribute impact.

The sanctuary is part of Peru’s national protected area system; a Management Unit (UGM) brings together ministries of culture, environment, tourism and local government. Despite this framework, coordination among agencies is challenging, and there are calls to harmonize legislation and reinvest more tourism revenue into infrastructure and conservation.

Getting to Machu Picchu

Acclimatize in Cusco and the Sacred Valley

Most journeys to Machu Picchu begin in Cusco, the former Inca capital and present‑day hub for Andean travel. Located at around 3,399 m (11,152 feet)–, Cusco is significantly higher than Machu Picchu. Spending several days here before trekking allows your body to produce more red blood cells and adapt to thinner air.

Use this time to explore Sacsayhuamán, Qorikancha, the San Blas neighbourhood, museums and markets. Day trips to Pisac, Moray, Maras and Chinchero in the Sacred Valley further aid acclimatization.

Train Options

The most comfortable way to reach Machu Picchu is by train from either Cusco (Poroy or San Pedro stations) or Ollantaytambo to Aguas Calientes. Two main companies, PeruRail and IncaRail, operate services with various classes.

Budget travellers may choose the Expedition or Voyager class; those wanting panoramic views book Vistadome or 360° coaches with large windows and traditional dance performances. Luxury seekers opt for the Hiram Bingham or First Class trains with gourmet dining and open‑air observation cars.

Travel time varies: Cusco (San Pedro) to Aguas Calientes takes about 3.5 hours; from Ollantaytambo the ride is roughly 1.5–2 hours, making the latter a popular departure point. Seats fill quickly in high season, so purchase tickets weeks or months ahead. Note that train companies often run bimodal services (bus plus train) during rainy season when tracks near Cusco can flood.

Bus, Van and Road Routes

If you’re adventurous or budget‑conscious, you can travel overland via Santa Maria and Santa Teresa to Hidroeléctrica. From Cusco, buses or colectivos run to the town of Santa Maria (6–7 hours) where you can catch vans or taxis through a winding road to Santa Teresa. From there, a shuttle goes to Hidroeléctrica station. The final segment is a 10 km (6 mile) walk along the train tracks to Aguas Calientes, taking about 2.5–3 hours. This route affords views of waterfalls and coffee farms but involves long travel days and basic infrastructure. Make sure landslides haven’t blocked roads during the rainy season.

From Aguas Calientes to the Citadel

Aguas Calientes, officially renamed Machu Picchu Pueblo, is a bustling town nestled in a narrow gorge beneath the site. Here you’ll find hotels, hostels, restaurants, hot springs and craft markets. To reach the citadel, you have two choices:

- Shuttle Bus: The Consettur buses depart every 10–15 minutes from the centre of town starting around 5:30 am. The ride up the Hiram Bingham Highway takes 25 minutes and costs around US$24 round‑trip (prices subject to change; confirm current policy). Lines form early in high season, so arrive at least an hour before your entry time.

- Hiking Trail: A stone staircase climbs 400 vertical metres from the Puente Ruinas (bridge) to the Machu Picchu entrance. The ascent takes 60–90 minutes, depending on fitness. Bring plenty of water, insect repellent and a rain jacket. Many trekkers hike up and ride the bus down to save their knees.

There is no road beyond Hidroeléctrica and no helicopter service inside the sanctuary—these restrictions protect the fragile environment and maintain the site’s serenity.

Understanding Tickets, Circuits and Entry Rules

Navigating ticketing for Machu Picchu can feel like deciphering an Inca calendar, but with patience and reliable information, you’ll secure the right permit.

Ticket Categories and Circuits

Peru’s Ministry of Culture sells several types of tickets, each tied to a circuit—a predetermined route that guides visitor flow and protects fragile areas. The main categories include:

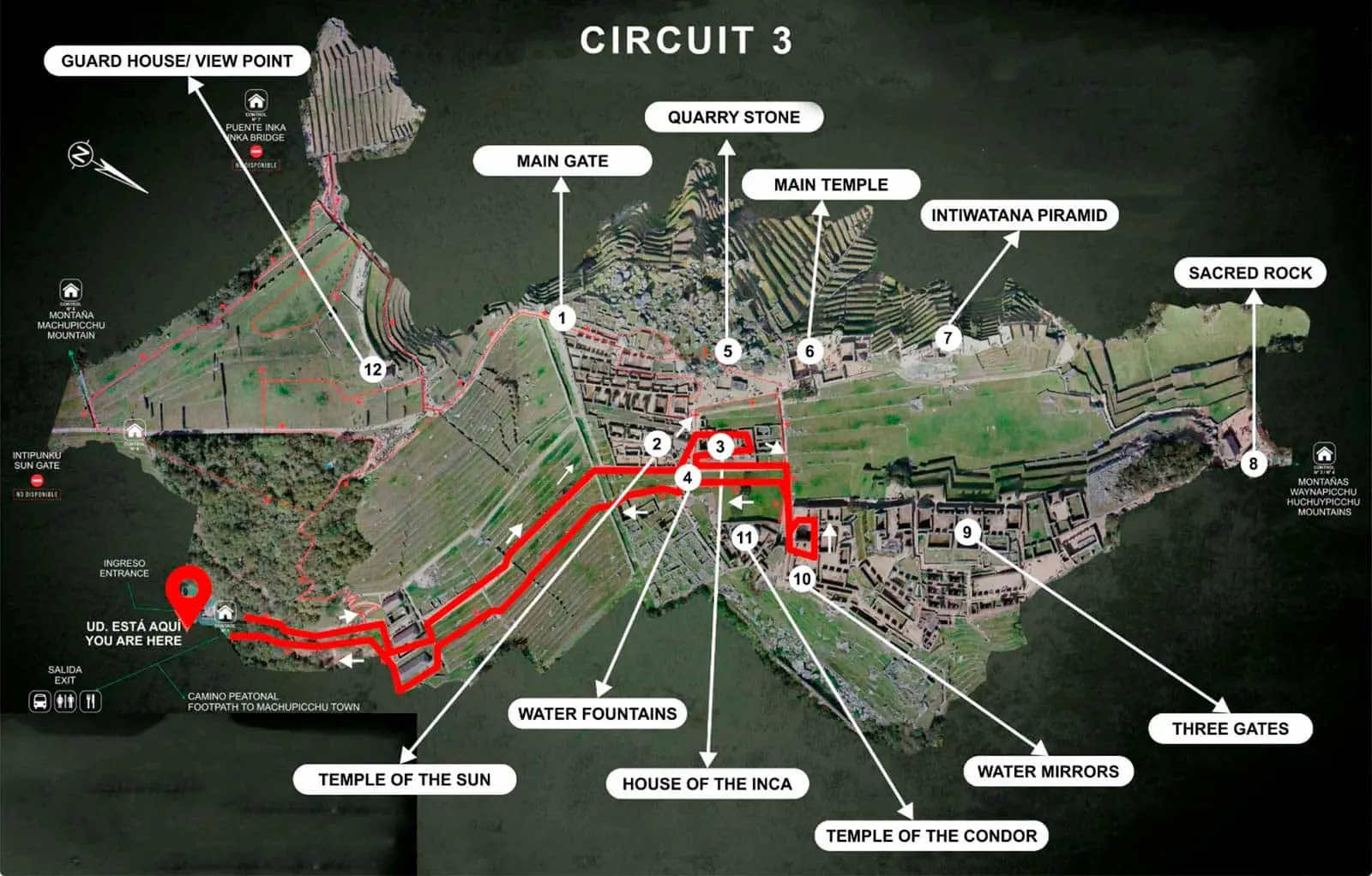

- Machu Picchu Llaqta (General Visit): Choose from circuits 1A, 1B, 2A, 2B, 3A, 3B, 4A and 4B. Circuit 1 focuses on the upper terraces and classic photo spots; Circuit 2 covers most of the site including the Sacred Plaza; Circuit 3 emphasises lower agricultural terraces and the Inca Bridge path; Circuit 4 explores the back sector. You cannot backtrack or revisit sectors once you exit.

- Machu Picchu + Huayna Picchu: Includes Circuit 4 plus the steep hike up Huayna Picchu. Permits are limited and sell out months in advance.

- Machu Picchu + Machu Picchu Mountain: Includes Circuit 3 and the trail to Machu Picchu Mountain, a longer but less exposed climb with sweeping views.

- Machu Picchu + Huchuy Picchu: A shorter climb to the small peak north of the citadel, ideal for those wanting a view without the vertigo of Huayna Picchu.

- Machu Picchu + Inca Bridge: Circuit 1 plus a short hike to the Inca Bridge, a stone path carved into a cliff face used historically to control access.

- Machu Picchu + Inti Punku (Sun Gate): Circuit 1 plus the hike to the original Inca Trail entrance; currently, access can change—confirm current policy.

Time Slots and Tolerances

As of mid‑2024, tickets are issued for specific entry times, starting hourly from 6 am to 3 pm. According to the Adios Adventure Travel update, visitors must enter at the exact time printed on their ticket; the previous one‑hour window no longer applies.

There is a 45‑minute grace period in high season and a 30‑minute tolerance in low season, but do not count on it. Once inside, the allowable stay is about 2–4 hours, depending on the circuit. Combined tickets with mountain hikes include an additional hour to reach the trailhead. There is no tolerance for lateness when checking in for Huayna Picchu or other hikes.

How to Purchase Tickets

Tickets can be purchased through:

- Official Government Website: The primary portal is cultura.pe (formerly machupicchu.gob.pe). It offers options in English and Spanish and accepts international cards. You must enter passport details, select a date and circuit, and download your ticket. Due to high demand, the site may crash; persistence is key.

- Authorized Ticket Offices: In Cusco and Aguas Calientes you can buy tickets in person. However, popular circuits and mountain hikes sell out quickly, so only rely on this for low season or general entrance.

- Tour Operators: Booking through Alpaca Expeditions or another licensed agency can save time. Operators often bundle permits with treks, transport and guides. They will handle the bureaucracy and ensure you have the correct circuit for your trek itinerary.

Required Documentation and Rules

- Passport: Carry the original passport you used to book your ticket; photocopies or expired passports are not accepted.

- Student ID: If claiming the student discount (usually for under‑25s), bring the original ISIC card. University IDs do not always qualify.

- Prohibited Items: Tripods, professional camera gear, drones, selfie sticks longer than 30 cm, umbrellas, large backpacks (over 40×35×20 cm), food, alcoholic beverages and aerosol sprays are not allowed. Walking sticks must have rubber tips. Small snack and water containers are permitted, but leave no trash behind.

- Re‑entry: Once you exit the citadel you cannot re‑enter on the same ticket, so visit the restroom (outside the gate) before starting your circuit.

- Guides: While not currently mandatory for general visits (confirm current policy), guides enhance the experience and are required for certain treks. Consider hiring a certified local guide or booking a tour with Alpaca Expeditions.

Circuits Explained

Peru introduced circuits to distribute visitors and protect vulnerable areas. Here is an overview of the six main circuits mentioned in the 2024 update:

| Circuit | Highlights | Duration |

| 1A/1B (Upper Circuit) | Guardhouse, terraces, Sun Gate viewpoint, Temple of the Sun (from above), Main Plaza, Intihuatana views | 2–2.5 hours |

| 2A/2B (Classic Circuit) | Most comprehensive route: Guardhouse, Sacred Plaza, Room of the Three Windows, Royal Residence, Temple of the Condor, Water Mirrors | 3–4 hours |

| 3A/3B (Lower Circuit) | Agricultural terraces, Inca Bridge, viewpoint of the main gate; less steep but fewer structures | 1.5–2 hours |

| 4A/4B (Circuit with Huayna Picchu or Huchuy Picchu) | Lower circuit plus access to Huayna Picchu or Huchuy Picchu; steep climb requiring a separate time slot | 3–5 hours |

| Gran Caverna & Great Cavern | Part of Circuit 3; includes a cave with carved seats known as the Temple of the Moon; reopened in 2024 (check availability) | 3–4 hours |

| Inti Punku Route | Hike to the Sun Gate from inside the park (shorter than the one on the Inca Trail); currently restricted to certain tickets (confirm current policy) | 3 hours |

Study the circuit maps in advance and choose based on your interests and physical ability. During high season, circuits 2A and 2B sell out fastest.

Trekking to Machu Picchu

Trekking through the Andes to reach Machu Picchu is as much a pilgrimage as it is a hike. Each route offers its own blend of scenery, culture and challenge. Below is a deep dive into the main options and how to decide among them.

Classic Inca Trail (4 days/3 nights)

The Classic Inca Trail is a 42 km (26-mile) route that follows original Inca paths and culminates at the Inti Punku (Sun Gate). Permits are strictly limited to 500 people per day, including guides and porters. The trail closes every February for maintenance. Tour companies like Alpaca Expeditions typically operate group departures between March and January.

Day 1: Start at Km 82 (Piscacucho) after a 3–4 hour drive from Cusco. Pass the ruins of Patallacta, cross the Urubamba River and camp at Wayllabamba (2,980 m). Distance: 12 km. Elevation gain is gradual, giving hikers time to adjust.

Day 2: The most challenging day. Climb steeply through cloud forest and puna grasslands to the infamous Dead Woman’s Pass (Warmi Wañusqa) at approximately 4,215 m. Pause to celebrate and descend to Pacaymayu camp at 3,600 m. Distance: 11 km.

Day 3: Enter the mystical realm of high‑altitude forests and ancient sites like Runkurakay, Sayacmarca, Phuyupatamarca (“the place above the clouds”) and Wiñay Wayna (“forever young”). This undulating day is long but rewarding. Camp near Wiñay Wayna at about 2,650 m. Distance: 16 km.

Day 4: Wake before dawn to reach Inti Punku in time for sunrise. Watching the first light spill over Machu Picchu is a transformative moment. After taking photos, descend to the checkpoint and enter the citadel through circuit 5 or 2, depending on current rules. Distance: 5 km.

The Inca Trail’s allure lies in its sense of continuity: you walk stone steps laid down six centuries ago, sleep under constellations that guided Inca astronomers, and arrive at Machu Picchu through the same gate used by original pilgrims. However, the high altitude and rugged terrain demand good fitness and proper gear.

Salkantay Trek (5–6 days)

Named after the glacier‑clad Nevado Salkantay (6,271 m), this trek is often called the Savage Mountain route. It reaches the Salkantay Pass at 4,600 m, passing turquoise lakes like Humantay and descending into cloud forest before linking to either the traditional train route or hiking to Aguas Calientes. Highlights include camping under starry skies, visiting coffee plantations and soaking in Santa Teresa hot springs. Unlike the Inca Trail, no permit is required, making bookings more flexible. However, the higher altitude and longer distances demand good acclimatization and porters or pack horses.

salkantay trek

Lares Trek (3–4 days)

The Lares Trek offers cultural immersion through remote Andean villages. Starting near the town of Lares (famous for its hot springs), hikers traverse high passes (around 4,400 m), glaciers, lakes and Quechua communities. You can meet weavers, learn about traditional textile techniques and see herds of alpacas and llamas grazing on puna grass. At the end, trekkers typically take a vehicle to Ollantaytambo and then the train to Aguas Calientes. The Lares trek is less crowded than the Inca Trail but equally demanding due to altitude.

Choquequirao to Machu Picchu (7–9 days)

For the ultimate adventure, combine two of Peru’s most stunning Inca sites. Choquequirao, often called the “sister city” to Machu Picchu, is a sprawling complex perched high above the Apurimac River. Few visitors make the strenuous 30 km trek to reach it, so you’ll likely have terraces and plazas to yourself. From Choquequirao, a rarely travelled route leads to Yanama, then joins the Salkantay Trail before reaching Aguas Calientes. Expect long days, camping and deep ravines. This is for experienced trekkers seeking solitude.

Inca Jungle and Other Options

The Inca Jungle Trek combines downhill mountain biking from Abra Malaga, white‑water rafting, zip‑lining and hiking through coffee plantations. It’s a fun, adrenaline‑packed alternative for travellers who want variety. Shorter treks like the Huchuy Qosqo or Moonstone Trail offer glimpses of Inca ruins without the crowds. You can also design bespoke routes, combining hiking with train rides.

Trek Comparison Table

| Trek | Duration | Highest Point | Difficulty | Permits Required | Highlights |

| Classic Inca Trail | 4 days | Dead Woman’s Pass (4,215 m) | Moderate–Challenging | Yes (500 permits/day) | Original Inca stone path, multiple ruins, Sun Gate entrance |

| Salkantay | 5–6 days | Salkantay Pass (4,600 m) | Challenging | No | Glacier views, Humantay Lake, cloud forest, hot springs |

| Lares | 3–4 days | Ipsaycocha Pass (~4,450 m) | Moderate–Challenging | No | Quechua villages, weaving communities, fewer tourists |

| Choquequirao to MP | 7–9 days | Yanama Pass (~4,700 m) | Hard | No (permit for Choquequirao may apply) | Remote ruins, Apurimac canyon, a combination of two citadels |

| Inca Jungle | 3–4 days | Abra Malaga (~4,330 m) | Moderate | No | Biking, rafting, zip‑lining, and coffee farms |

Permits, Porters and Porter Welfare

The Porter Protection Law in Peru stipulates that trek operators must provide porters with proper clothing, shelter and a maximum load of 20 kg (44 lbs). Inspections are conducted by SUNAFIL (National Superintendency of Labour Inspection). At the checkpoint at Km 82, officials weigh each porter’s pack to ensure compliance.

Trekking companies that ignore these regulations can lose their license. Additionally, pack animals are banned on the Inca Trail to preserve its stone steps. When choosing an operator, inquire about porter conditions, wages, insurance and social projects. Tipping is customary: collectively US$25 per porter and US$30 for the cook– is a guideline, though you may adjust based on service.

Preparing for Your Trek

- Physical Training: Begin endurance training several months before your trek. Incorporate hiking with a loaded backpack, cardiovascular workouts and stair climbing. Practice walking in your boots to avoid blisters.

- Acclimatization: Spend at least 2–3 days in Cusco or the Sacred Valley to adjust to altitude. Some travellers schedule a one‑day acclimatization hike to a site like Rainbow Mountain or Humantay Lake.

- Gear: Invest in broken‑in hiking boots, a comfortable backpack with rain cover, moisture‑wicking clothing, a warm jacket, rain gear, trekking poles with rubber tips, a headlamp, gloves and a hat. For camping treks, most companies provide tents, sleeping mats and cooking equipment; you can usually rent sleeping bags.

- Nutrition: Eat carbohydrate‑rich foods and stay hydrated. Coca tea and candies may help with altitude, and Ginkgo biloba supplements are said to reduce symptoms. Avoid alcohol during acclimatization.

- Mental Preparation: Weather can change quickly. Prepare for rain, heat and cold. Flexibility and positive attitude are essential; some days will test your limits.

Exploring the Citadel-Layout and Highlights

Entering Machu Picchu is like stepping into a stone tapestry woven across a mountain ridge. Each sector has a story, and understanding them enriches the experience.

Navigating the Site

The site divides broadly into agricultural terraces on the slopes and an urban sector on flatter ground. The urban sector further splits into royal/residential, religious, astronomical, industrial and administrative areas. Because circuits control your path, familiarize yourself with landmarks beforehand. Below is an overview of key features.

| Structure | Description and Significance |

| Guardhouse and Terraces | Upon entering on circuits 1 or 2, you climb to the Guardhouse for the classic panorama of terraces cascading down the mountainside, the urban core in the middle and Huayna Picchu beyond. These terraces prevented erosion and provided crops like maize and potatoes. |

| Main Gate and Calle Principal | The original entrance, reinforced with trapezoidal stones, opens to a wide street that divides residential from ceremonial sectors. |

| Temple of the Sun (Torreón) | A semicircular tower built on a granite outcrop. Its window aligns with the June solstice sunrise; the lower chamber served as a royal tomb or shrine. Visitors on circuit 1 glimpse it from above; access may be restricted to protect the fragile stone. |

| Royal Residence (Palace of the Inca) | Cluster of finely finished rooms with carved niches, drainage channels and a private courtyard. Likely the emperor’s quarters during visits. |

| Sacred Plaza and Room of the Three Windows | A ceremonial plaza flanked by three large trapezoidal windows representing the heavens, earth and underworld. Rituals and important meetings occurred here. |

Intihuatana Stone |

A carved pillar whose name means “hitching post of the sun.” Archaeologists believe it functioned as an astronomical clock, aligning with solstices. Visitors used to touch it for spiritual connection; now it is roped off for preservation. |

| Main Temple | Massive three‑walled structure with some of the finest masonry at the site. Its slightly shifted stones may reflect seismic activity during construction. |

| Temple of the Condor | Integrates natural rock formations with carved stone to depict a condor, symbolizing the sky realm. Beneath is a small underground chamber that might have served as a prison or ceremonial space. |

| Industrial Sector | Includes workshops where craftsmen produced tools, textiles and pottery. You can see remains of stone channels and storage rooms. |

| Water Fountains | A series of 16 fountains channels springwater along a stone staircase. The flow demonstrates Inca hydraulic engineering. Visitors can hear the gentle sound of water throughout the urban sector. |

| Inti Punku (Sun Gate) | Not within the citadel itself but accessible via a path on the Inca Trail or certain circuits. It was the original entrance for pilgrims arriving from Cusco. From here, the entire site is visible, framed by mountains and sky. |

| Inca Bridge | A narrow stone path carved into a cliff, originally used to control access from the western slope. A removable wooden plank once bridged a gap; invading armies would plunge if they tried to cross. |

Etiquette, Photo Tips and Accessibility

- Stay on the Path: The circuits exist to protect ruins. Avoid stepping on walls or terraces. Do not move or stack stones.

- Be Patient: Allow faster groups to pass and maintain space between groups to reduce congestion.

- Photography: Early morning and late afternoon provide softer light. Use the rule of thirds to frame the citadel with mountains. Drones are prohibited. For high‑angle shots, climb Huayna Picchu or Machu Picchu Mountain.

- Respect Sacred Sites: The temples are places of cultural significance. Keep voices low, avoid music, and dress respectfully (no exposed midriffs). You may see locals performing traditional offerings—observe quietly.

- Accessibility: The citadel includes many steep stairs and uneven surfaces. While there is no wheelchair access inside, travellers with limited mobility can enjoy partial views from the upper terraces or by staying in the lower circuit. Assistive personnel or portable chairs may be available upon request; contact the Ministry of Culture or your tour operator well in advance.

Weather, Seasons and Best Times to Visit

Deciding when to visit Machu Picchu depends on your priorities: clear skies, lush landscapes, cultural festivals or quiet trails. The Andes deliver surprises year‑round, but understanding patterns helps manage expectations.

Month‑By‑Month Guide

- January: Peak rainy season. Frequent showers saturate the cloud forest, making the site slippery but verdant. Ideal for photographers who love misty moods. The Inca Trail remains open but can be muddy.

- February: Wettest month and the Inca Trail is closed for maintenance and safety. Alternative treks operate, and crowd levels at Machu Picchu drop slightly. Expect rain, potential landslides and train delays. Carry waterproof gear.

- March: Rain persists early in the month and subsides toward the end. Wildflowers bloom. Availability for tickets and hotels is good.

- April: Shoulder season. Rain decreases, skies clear and temperatures are mild. Terraces are green and waterfalls are full. An excellent time to hike before the crowds arrive.

- May: Start of dry season. Crisp mornings, sunny days and moderate visitor numbers. Trails dry out, making treks easier. The Andean cross festival (Cruz Velakuy) occurs in some towns.

- June: Clear weather and Inti Raymi, the Inca festival of the sun, is celebrated on June 24 in Cusco. Expect high demand for tickets and accommodations. Days are sunny; nights are cold.

-

July: High season continues. Peru’s Independence Day (Fiestas Patrias) on July 28–29 brings national tourists. Book everything well ahead. Hikes are dry but busy.

- August: Still dry and busy. Wildfires can occur in dry grasslands, causing haze. The Virgin of Asunción festival occurs mid‑month in many Andean communities.

- September: Shoulder season begins as the dry season wanes. Mornings may have mist that clears to blue skies. Fewer crowds, pleasant temperatures and blossoming orchids.

- October: Transition month with variable weather. Rains return gradually, reviving vegetation. Attendance remains moderate. Great for those who enjoy changeable skies.

- November: Rainy season resumes. Fewer tourists, discounted rates and lush scenery. Some mountain hikes may close if conditions worsen. Bring rain gear.

- December: Festive month with Christmas celebrations in Cusco. Rain increases. A good time to experience Andean holiday traditions with fewer visitors.

Daily Timing and Light

Within any month, the time of day shapes your experience. Early morning (6-8 am) offers cooler temperatures, fewer people at viewpoints and the chance to see sunrise from the Sun Gate or terraces. Late morning and midday bring brighter light that accentuates the stonework but also larger crowds. Afternoon (12-3 pm) often sees clouds rolling in; however, many day‑trippers leave by early afternoon, opening quieter moments. Weather can shift quickly—carry a poncho and sunhat regardless of season.

Festival Calendar and Local Events

Coordinating your visit with a cultural festival adds depth to your trip. Major events include Inti Raymi (June 24 in Cusco), Qoyllur Rit’i (a pilgrimage in May/June combining Catholic and Andean traditions), Virgin of Carmen (July 15–18 in Paucartambo) and All Saints’ Day (November 1–2). During these times, transport and accommodation book out quickly, and some locals may be travelling themselves.

About Machu Picchu culture

Altitude, Health and Safety

Understanding Altitude Sickness

Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) occurs when the body struggles to adapt to decreased oxygen at high elevations. Even though Machu Picchu’s elevation is 2,430 m, travellers often arrive from Cusco at 3,399 m. Symptoms can include headaches, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, fatigue and shortness of breath. Severe forms—High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) and High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE)—are rare but life‑threatening.

Prevention and Management

- Ascend Gradually: Spend at least two nights in Cusco or the Sacred Valley before ascending higher. Take day trips to lower elevations rather than rushing to Dead Woman’s Pass on day 1.

- Hydrate and Eat Carbohydrates: Drink 2–3 litres of water per day and avoid excessive caffeine or alcohol. Eat light meals rich in carbohydrates to aid acclimatization.

- Medication: Consult a doctor about taking acetazolamide (Diamox), which accelerates acclimatization. Start 24 hours before ascent. Side effects may include tingling fingers and increased urination.

- Natural Remedies: Indigenous Peruvians chew coca leaves or drink coca tea. Another supplement, Ginkgo biloba, may reduce symptoms. These are adjuncts, not cures.

- Rest and Oxygen: Move slowly, especially on stairs. Many hotels in Cusco provide oxygen cylinders. Portable oxygen bottles can be purchased, but use them judiciously; rely primarily on acclimatization.

- Know When to Descend: If symptoms worsen or include confusion or fluid in the lungs, descend immediately and seek medical help.

General Health and Safety Tips

- Vaccinations: No specific immunizations are required for Machu Picchu, but consider Hepatitis A, Typhoid and routine vaccinations. Yellow fever vaccination is recommended if you extend your trip into the Amazon.

- Travel Insurance: Purchase comprehensive insurance covering trekking up to high altitude and emergency evacuation.

- Sun Protection: High altitude increases UV exposure. Wear sunscreen, sunglasses with UV protection and a brimmed hat.

- Insect Protection: Mosquitoes are common, especially in the rainy season. Use repellent with DEET or picaridin, wear long sleeves and consider permethrin‑treated clothing.

- Sanitation: Restrooms are only available outside the Machu Picchu gate. Bring small denominations of Peruvian soles to pay the fee. Carry hand sanitizer and use wipes for personal hygiene. All rubbish must be packed out.

- Trail Etiquette: Yield to porters and pack animals on alternative treks. Do not carve into rocks or pick plants. Respect quiet hours at campsites. Follow your guide’s instructions.

- Emergency Contacts: Make note of local emergency numbers, the location of clinics in Aguas Calientes and hospitals in Cusco. Guides carry first aid kits and are trained in wilderness medicine.

Packing List and Gear

Packing wisely makes the difference between comfort and misery in the Andes. Use this checklist as a starting point and adapt it to your trip length, season and trek style.

Printable Packing Checklist

| Category | Items |

| Documentation | Passport (original, waterproof pouch), permits and tickets, travel insurance papers, vaccination card, photocopies of documents |

| Money & Payments | Cash in small denominations (Peruvian soles), credit/debit cards, hidden money belt |

| Clothing-Base Layers | Moisture‑wicking T‑shirts, thermal underwear (for cold nights), and long‑sleeved shirts for sun protection |

| Clothing-Insulation | Fleece jacket or down sweater, lightweight puffer jacket, hat and gloves |

| Clothing-Outer Layers | Waterproof/breathable rain jacket, rain pants, poncho |

| Clothing-Bottoms | Convertible hiking pants, leggings, shorts for lower elevation, camp pants |

| Footwear | Broken‑in hiking boots (waterproof), camp shoes or sandals, extra socks (synthetic or wool), gaiters (optional) |

| Accessories | Wide‑brim hat or cap, buff or scarf, sunglasses, trekking poles with rubber tips, lightweight gloves |

| Gear | Daypack (20–30 L), rain cover, waterproof dry bags or ziplock bags, water bottles (reusable), water purification tablets or filter, headlamp with extra batteries, sleeping bag (rated to –5 °C for dry season), sleeping pad (if not provided), inflatable pillow |

| Electronics | Camera or smartphone, extra memory cards, portable charger/power bank, travel adapter (220V in Peru) |

| Toiletries & Health | Toothbrush, biodegradable soap, quick‑dry towel, sunscreen (SPF 30+), lip balm with SPF, insect repellent, hand sanitizer, wet wipes, small first aid kit (band‑aids, blister plasters, ibuprofen, anti‑nausea tablets, Diamox if prescribed), prescription medications, altitude sickness remedies (coca candies, Ginkgo biloba), toilet paper in ziplock bag |

| Extras | Snacks (energy bars, nuts, dried fruit), journal and pen, cards or small games, Spanish/Quechua phrasebook, reusable shopping bag for local markets |

Packing Tips

- Layering is Key: Temperatures vary widely from midday sun to cold nights. Wear layers that can be added or removed easily.

- Weight Management: On the Inca Trail, porters carry the group gear, but personal load should be under 7 kg if you hire an extra porter; otherwise, plan to carry your own pack. On alternative treks, horses may carry luggage—check with your operator.

- Leave Valuables Behind: Secure passports and cash in hotel safes when not needed. Do not bring expensive jewellery or unnecessary electronics.

- Dry Bags: Use dry bags or waterproof pouches to protect documents and electronics from rain. Luggage often gets exposed during transport.

- Resupply in Cusco: Forgot something? Cusco has gear shops where you can buy trekking poles, hats, gloves and rental sleeping bags. Aguas Calientes has basic supplies but at higher prices.

Itineraries and Trip Planning

No two Machu Picchu trips are the same. Tailor your journey to your interests, fitness and time. Below are sample itineraries with suggested pacing.

One‑Day Express Visit

- Day 1: Fly or bus to Cusco and immediately transfer to Ollantaytambo (2 hr) to avoid altitude. Take the afternoon train to Aguas Calientes, spend the night.

- Day 2: Catch an early bus to Machu Picchu for a 7 am entry. Follow Circuit 1 or 2, exit by midday. Have lunch in Aguas Calientes and take the afternoon train back to Cusco or Ollantaytambo. Note that this fast itinerary offers little acclimatization—best for travellers already acclimatized at other high‑altitude destinations.

Two‑Day Train Trip

- Day 1: Arrive in Cusco, spend the day exploring. Overnight.

- Day 2: Take a morning train from Cusco or Ollantaytambo to Aguas Calientes. Enjoy the town’s hot springs and craft market. Sleep early.

- Day 3: Enter Machu Picchu with a morning ticket. Explore for 3–4 hours. Lunch and train back to Cusco. Ideal for those wanting a more relaxed pace and some acclimatization.

Four‑Day Classic Inca Trail Trek

- Day 1: Cusco-Km 82-Wayllabamba. Gentle hiking through villages and terraces.

- Day 2: Wayllabamba-Dead Woman’s Pass-Pacaymayu. The toughest climb, but porters cheer you on.

- Day 3: Pacaymayu-Runkurakay-Phuyupatamarca-Wiñay Wayna. Visit multiple ruins and experience cloud forests.

- Day 4: Wiñay Wayna-Inti Punku-Machu Picchu. Arrive for sunrise and take a guided tour.

Five‑Day Salkantay + Machu Picchu

- Day 1: Cusco-Mollepata-Soraypampa. Hike to Humantay Lake; camp under Salkantay.

- Day 2: Soraypampa-Salkantay Pass-Wayracmachay. Summit the highest point and descend into cloud forest.

- Day 3: Wayracmachay-Collpapampa-La Playa. Walk through bamboo forests and coffee plantations.

- Day 4: La Playa-Llactapata-Hidroeléctrica-Aguas Calientes. Visit Llactapata ruins overlooking Machu Picchu.

- Day 5: Machu Picchu visit via bus or climb.

Week‑Long Sacred Valley & Machu Picchu Adventure

- Day 1–2: Explore Cusco’s sites and acclimatize.

- Day 3: Visit Pisac ruins and market; overnight in the Sacred Valley.

- Day 4: Tour Moray circular terraces and Maras salt pans; overnight in Urubamba.

- Day 5: Explore Ollantaytambo fortress and board an afternoon train to Aguas Calientes.

- Day 6: Visit Machu Picchu; optional Huayna Picchu hike.

- Day 7: Return to Cusco and fly home or continue to another region.

Special Interest Variations

- Family Travel: Choose trains or easier treks like the 2‑day Inca Trail. Include educational stops at local weaving co‑operatives.

- Photographers: Spend two days at Machu Picchu with morning and afternoon entries to capture changing light. Bring a tripod only if permitted (confirm current policy) and respect no‑flash rules.

- Birdwatchers: Add a day in the cloud forest below Machu Picchu or at Manu National Park for endemic species.

- Cultural Enthusiasts: Book community‑based stays in Amaru or Patacancha, where you can learn traditional weaving and participate in a Pachamama blessing.

Booking Timeline and Practical Tips

- 6–12 Months Ahead: Decide travel dates, research treks, book flights and Inca Trail permits if required.

- 3–6 Months Ahead: Reserve train tickets and hotels, especially during high season. Plan for festival dates.

- 1–2 Months Ahead: Purchase Machu Picchu tickets, hire guides or trekking companies and arrange travel insurance.

- 2 Weeks Ahead: Finalize packing, copies of documents and emergency contacts. Confirm current policies on entry times and circuits.

- During Travel: Keep digital and physical copies of permits. Stay flexible; weather or strikes may disrupt schedules. Work with local operators who can rearrange logistics.

Thoughtful planning ensures that once you reach the Sacred Mountain, you can focus on the experience rather than logistics.

Sustainability and Responsible Travel

Machu Picchu’s popularity poses a paradox: the influx of visitors provides income for local communities and funds conservation, yet too many feet can damage the very heritage people come to see. Responsible travel minimizes harm and amplifies benefits.

About Machu Picchu Porters

Tourism Impact and UNESCO Concerns

UNESCO has repeatedly warned that overcrowding, uncontrolled development and environmental degradation threaten Machu Picchu’s Outstanding Universal Value. Daily visitor numbers have been capped and circuits introduced to disperse traffic. Despite these measures, there are concerns about erosion of terraces, litter, human waste and strain on water resources. Supporting sustainable practices helps protect the site for future generations.

Leave No Trace Principles

- Plan Ahead and Prepare: Research current rules, book permits in advance and carry only permitted items. Pack reusable water bottles and utensils to reduce waste.

- Travel and Camp on Durable Surfaces: Stay on marked paths, use designated campsites and avoid cutting switchbacks on the trail.

- Dispose of Waste Properly: Carry a small bag for your rubbish, including toilet paper. Pack out everything you bring in.

- Leave What You Find: Do not remove stones, plants or artefacts. Avoid carving names into wood or rock.

- Minimize Campfire Impact: On treks, use camping stoves. Fires scar the landscape and consume scarce wood.

- Respect Wildlife: Observe animals from a distance. Do not feed wildlife or stray dogs in Aguas Calientes.

- Be Considerate of Other Visitors: Keep noise levels down, yield to hikers going uphill and follow guide instructions.

Porter Welfare and Ethical Trekking

As highlighted earlier, Peru’s Porter Protection Law mandates that porters receive proper clothing, fair pay and carry no more than 20 kg–. Choose companies—like Alpaca Expeditions—that openly discuss porter welfare, provide insurance and invest in community projects. Consider carrying part of your own gear and tipping generously–. Porters often come from rural Quechua villages; your respect and gratitude contribute to their dignity.

Community Engagement

Responsible tourism involves supporting local economies beyond the main tourist hubs. Buy handicrafts directly from artisans in villages like Chinchero and Pisac. Visit cooperatives where women weave textiles using traditional techniques. Stay in family‑run lodges or homestays in Ollantaytambo or Patacancha. Learn a few words of Quechua; greetings like “rimaykullayki” (hello) and “sulpayki” (thank you) foster connection.

Environmental Initiatives

Several organisations are working to restore Andean forests and improve waste management. Planting native species like Polylepis trees helps prevent erosion and provides habitat for birds. Alpaca Expeditions and partners run reforestation programmes where travellers can volunteer to plant seedlings.

Join a clean‑up trek or donate to conservation funds. Taking the train instead of road routes reduces carbon emissions. By travelling responsibly, you contribute to the long‑term health of the sanctuary and the well‑being of its people.

Beyond Machu Picchu-Additional Experiences

While Machu Picchu is the crown jewel, the surrounding sites enrich your understanding of Inca history and Andean culture.

Sacred Valley Highlights

The Sacred Valley of the Incas stretches along the Urubamba River between Pisac and Ollantaytambo. Fertile soils and a mild climate made it the empire’s breadbasket. Today, the valley hosts archaeological sites, markets and Andean villages.

- Pisac: Known for its agricultural terraces shaped like partridges and a bustling market selling textiles, ceramics and jewellery. Above the town lies a fortress with temples and ceremonial baths.

- Ollantaytambo: A living Inca town with an impressive fortress that served as a military stronghold. Its stepped terraces, ceremonial centres and water channels illustrate Inca engineering. Many trekkers start their Inca Trail here.

- Moray: Circular depressions with concentric terraces that functioned as an agricultural laboratory, allowing the Inca to experiment with microclimates.

- Maras: Salt pans cascading down a hillside, where families still harvest salt using ancient techniques. The white pools contrast beautifully with the red mountains.

- Chinchero: Home to a colonial church built atop an Inca palace, as well as weaving cooperatives where women demonstrate dyeing and loom work.

Cusco and Surrounds

Cusco merits at least a few days. The Plaza de Armas, Cathedral and Jesuit Church dominate the city centre. Explore San Blas’ artists’ quarter, visit Sacsayhuamán with its cyclopean stones, and wander the San Pedro Market for local produce and street food. Nearby Qenqo, Puka Pukara and Tambomachay round out the four major ruins on the outskirts. Museums like the Museum of Pre‑Columbian Art and the Qorikancha Museum provide context for Inca religion and Spanish colonization.

Rainbow Mountain and Humantay Lake

Vinicunca (Rainbow Mountain) dazzles with stripes of red, ochre and turquoise caused by mineral deposits. At over 5,000 m, it requires acclimatization and a 10 km hike, but the view is spectacular. Humantay Lake, a turquoise glacial lake at 4,200 m on the Salkantay route, offers a challenging but shorter hike. Both can be done as day trips from Cusco.

Other Inca Sites

- Choquequirao: Larger than Machu Picchu but far less visited. Its terraces cascade down cliffs; the trek is demanding but rewarding.

- Vitcos and Rosaspata: Sites along the Vilcabamba trail, considered part of the last Inca refuges.

- Espíritu Pampa: Deep in the rainforest and hard to reach, this archaeological site is associated with the rebel emperor Tupac Amaru and the final days of Inca resistance.

By exploring beyond the citadel, you weave a richer tapestry of stories and landscapes, turning a single destination into a comprehensive cultural journey.

Practicalities and FAQs

Budgeting and Costs

Costs vary depending on travel style. Here’s a rough breakdown (all prices subject to change—confirm current policy):

- Machu Picchu Entry Ticket: US$50–$70 for foreign adults; discounts for students and Andean Community citizens.

- Huayna Picchu or Machu Picchu Mountain Add‑On: Additional US$15–$20.

- Train Tickets: US$65–$200 one way depending on class and departure point.

- Bus Aguas Calientes–Machu Picchu: US$12–$24 round‑trip.

- Inca Trail Trek: US$650–$1,000 per person for a four‑day trek, including permits, porters, guides and food. Prices reflect porter welfare and small group sizes.

- Alternative Treks: US$350–$800 depending on duration and services.

- Hotels: Budget hostels in Cusco and Aguas Calientes from US$15/night; midrange hotels around US$50–$100; luxury lodges US$200+.

- Meals: US$5–$15 for basic dishes, US$30+ for upscale restaurants.

- Tips: Budget US$5–$10 per day for guides, porters, cooks and drivers.

Plan for contingencies such as flight delays, strikes or medical expenses. Carry a mix of cash and cards; ATMs are available in Cusco and Aguas Calientes but sometimes run out of cash.

Communication and Connectivity

Spanish is Peru’s official language, but in rural communities, many people speak Quechua. Learn basic phrases or travel with a guide who can translate. English is widely spoken in tourist areas. Mobile coverage is decent in Cusco and Aguas Calientes; however, the Inca Trail and remote treks have limited or no signal. Purchase a local SIM card (Claro, Movistar, Entel) if you need data. Wi‑Fi is available in most hotels and some restaurants, though speeds vary.

Health and Hygiene

Clean drinking water is scarce; treat or boil water or use a filter. Stick to bottled or filtered water in restaurants. Food hygiene is generally good in reputable establishments, but avoid raw salads and unpeeled fruit from street stalls if you have a sensitive stomach. Wash hands frequently and carry hand sanitizer. The single restroom outside the Machu Picchu gate costs a small fee—bring coins.

Cultural Etiquette

- Greetings: A simple “hola” (hello) or “rimaykullayki” in Quechua is polite. Shake hands or hug if offered.

- Dress: Wear modest clothing in villages and sacred sites. Swimwear is acceptable only at hot springs.

- Photography: Always ask before photographing people, especially elders and children. Some may ask for a small tip.

- Bargaining: Haggling is expected at markets but keep it friendly. Remember that a few soles mean more to artisans than to you.

- Pachamama Respect: Many Andean people make offerings to Earth Mother. Do not litter or disrespect sacred mountains (apus).

Safety Concerns

Peru is generally safe, but petty theft occurs in crowded areas. Keep your valuables secure and be aware of pickpockets. Use licensed taxis or ride‑share apps rather than hailing cars on the street. At night, stick to well‑lit areas. On treks, follow your guide and do not wander off. Natural hazards include landslides, floods and sudden storms. In remote areas, cell service is unreliable—carry a whistle and flashlight.

Accessibility for All Ages

Machu Picchu can be visited by travellers of various ages with some planning. Families with children should pace the trip slowly, bringing snacks, games and sun protection. Teenagers often enjoy the challenge of trekking.

For older travellers, consider the train option and book a private guide for personalized pacing. Those with limited mobility may access partial views from the upper terraces or by hiring specialized assistance. Always consult a doctor before travelling at high altitude.

Answers to Remaining FAQs

Below are concise answers to several common questions not covered elsewhere:

- Are drones allowed? Drones are prohibited within the Historic Sanctuary to protect wildlife and visitor privacy.

- Can I camp at Machu Picchu? Camping inside the site is not allowed. Trekkers camp along the Inca Trail at designated sites.

- Is there food inside the site? Food is not sold or allowed inside; bring snacks and eat them discreetly. Picnic areas are not provided.

- How early should I line up for the bus? During high season, arrive at the Consettur bus stop at least an hour before your entry time to account for queues.

- Do I need a guide? Guides are recommended for a richer experience and required on the Inca Trail. Day visitors can enter without a guide (confirm current policy), but hiring one supports the local economy.

- Is water available on the trail? On the Inca Trail, porters or cooks boil water at camps. Bring purification tablets for an extra supply.

- What if I miss my train? Tickets are time‑specific. If you miss your train, visit the ticket office to rebook (subject to availability) and expect a fee.

Planning ahead and staying flexible will help you navigate any situation gracefully.

Glossary of Quechua and Inca Terms

Understanding local terms deepens your connection to the culture. Pronunciations are approximate.

| Term | Pronunciation | Meaning |

| Apu | AH‑poo | Sacred mountain spirit. Locals make offerings to apus for protection. |

| Chicha | CHEE‑cha | Fermented corn beer consumed during ceremonies. |

| Inti | IN‑tee | Sun god, one of the principal deities of the Inca pantheon. |

| Intihuatana | in‑tee‑hwa‑TAH‑na | “Hitching post of the sun.” A carved stone used as an astronomical marker. |

| Llaqta | YAK‑ta | A settlement or town; official name for the Machu Picchu citadel. |

| Pachacuti | pa‑cha‑KOO‑tee | Ninth Inca emperor is credited with expanding the empire and ordering construction of Machu Picchu. |

| Pachamama | pa‑cha‑MA‑ma | Earth Mother: Andean goddess of fertility and agriculture. |

| Puka Pukara | POO‑ka POO‑ka‑ra | “Red Fortress,” a ruin outside Cusco. |

| Quechua | KEH‑chwa | Indigenous language family spoken in the Andes; also the people who speak it. |

| Rumi | ROO‑mee | Stone appears in names like Runkurakay. |

| Runkurakay | roon‑koo‑ra‑KAI | An Inca archaeological site on the Inca Trail. |

| Sapa Inca | SA‑pa IN‑ka | Emperor of the Inca Empire, considered divine. |

| Tambu/Tambo | TAM‑boo | Way station or rest house on Inca roads. |

| Urubamba | oo‑roo‑BAM‑ba | The river that flows through the Sacred Valley. |

| Wiñay Wayna | WEEN‑yai WAY‑na | “Forever young”; name of a ruin and an orchid on the Inca Trail. |

| Warmi Wañusqa | WAR‑mee wa‑NYOOS‑ka | “Dead Woman’s Pass” is the highest point on the Classic Inca Trail. |

| Yanantin | ya‑NAN‑teen | Principle of duality and complementary opposites in Andean cosmology. |

Use these words respectfully; learning even a few can earn smiles and appreciation from locals.

Conclusion

Machu Picchu inspires wonder because it bridges worlds: past and present, human ingenuity and natural splendour, ambition and humility. The Inca builders set stones without mortar, aligned temples with solstices and created terraces that seem to grow out of the mountain itself.

Centuries later, UNESCO recognises the sanctuary’s dual importance as a cultural treasure and a biodiversity hotspot. Yet this very fame subjects the site to intense pressures. Responsible travellers must tread lightly and purposefully.

As you plan your journey, remember that Machu Picchu is not a single photo opportunity but an immersive experience that unfolds over days of acclimatization, trekking, learning and reflection. Use the itineraries and checklists provided to tailor your trip.

Choose ethical operators like Alpaca Expeditions that prioritize porter welfare and sustainability.

Engage with local communities, learn a few Quechua words and savour the flavours of Andean cuisine. Whether you arrive by train or trek through cloud forests, when you finally glimpse the citadel through the mist, you’ll appreciate not just its beauty but the layers of history and effort that brought you there.

Your adventure begins with curiosity. Let this guide be your roadmap and inspiration. Confirm current policies before you go, pack mindfully and travel respectfully. When you return, share your stories and help protect this sacred place for future explorers.

Alpaca Expeditions Recognitions

ISO (International Organization for Standardization)

In the pursuit to stand out from the rest, Alpaca Expeditions has obtained four ISOs plus our carbon footprint certificate to date. These achievements result from our efforts to implement the internationally-recognized integrated management system. They also represent our commitment to all of our clients and staff of operating sustainability and responsibility in every way possible.

Porters will carry up to 7 kg of your personal items, which must include your sleeping bag and air mat (if you bring or rent one). From us, these two items weigh a combined total of 3.5 kg.

Porters will carry up to 7 kg of your personal items, which must include your sleeping bag and air mat (if you bring or rent one). From us, these two items weigh a combined total of 3.5 kg.